Adventures on the Path of Modern Day (Female) Guru Yoga

26

Oct 2023

By Cara Conroy-Lau

Editor: Erika Rasmussen

What does your mind follow? Your stories, your job? Your relationship? What you want to eat next? Transient feelings of crabbiness, anger, or fear?

Has your mind ever followed a person? Trained on a mindstream? Like a dog on a scent?

When I came into this Dharma lineage about 18 years ago, Qapel (then Doug Sensei) was the principal Teacher. Catherine Sensei was not teaching formally.

In our Dharma tradition, the relationship with one’s Teacher, guru, or spiritual mentor is of upmost importance. To me, they’re like the red tugboats that I watched in Wellington’s stormy harbour as a child—a trusty guide through the heavy seas of one’s conditioning and pain.

Over the past decade, there has been a shift. Catherine Sensei evolved into a teacher; my Teacher. I could not have imagined how enriching, challenging and always surprising the journey with her has been.

And this summer, I received a precious gift. In July, I travelled across the globe from Clear Sky in Canada to be an attendant to Catherine Sensei in Kyoto, Japan. It was time for the Gion Matsuri festival, which she has been documenting and writing about for 30 years.

I observed Sensei being Dharma attendant, consort, and Teacher over many years. Her role as Gion Matsuri researcher, writer, and community member, however, has been mysterious, in a different way. This would be the first time I’d witness it.

I met Sensei at the airport in Tokyo, where we got straight into a Shinkansen bullet train to Kyoto and into Gion Matsuri mode. She was a powerhouse, right off the tarmac.

Riding her elegant coattails, I entered a new realm with her. For 1,150 years—since the year 869, a year of terrible epidemic—people have come together in the height of the summer, July, to ward off “evil spirits,” disease, and pestilence, and to nurture the wholesome and positive, a.k.a., health—spiritual and physical. And here we were, in 2023, about to continue that process and practice.

In the heart of downtown Kyoto, Sensei and I entered the quaint AirBnB she’d booked us, a traditional style ‘machiya’ house complete with tatami grass mat rooms and sliding paper doors. If you aren’t familiar with this, think Memoirs of a Geisha—ish!

My alarm rings at 6am. I wake in the small wood-and-plaster tatami room, next to Sensei’s through the paper-thin sliding walls. The ceiling slopes low. I hit my head a couple of times. It is cute, like an attic, and I feel I am tucked away in a cocoon, sensing Sensei through the walls, hearing her wake up, stir, move about, rest, sleep.

By now, a typical day, Sensei is up, meditating, stretching, preparing. I would creep down the creaking stairs to the small Japanese washroom, trying not to disturb her, focused on washing off the residual sweat from the hot summer night previous.

Typically bleary eyed in the mornings, proud of myself for being on! so early; yet, noticing where I was still cutting it close, getting the camera gear ready just in time to get out the 7am door… How can I do better? Sensei shares: She needs me to be even sharper. On top of time management, helping her with the clock schedule we set, sharp sharp sharp—Saturn Saturn Saturn—to achieve our intentions for the day.

Out we go, into the morning, not yet breaking the night’s fast. It is peaceful, humid, warm on the Kyoto streets, as if the city itself was yawning, preparing for the soon to be searingly hot day with a sleepy smile.

A tripod and camera drape over my shoulder and a rather heavy baby-pink camera bag rides my back. It is baby-pink to challenge my serious sensibilities of coolness. I wouldn’t have been caught dead with a baby-pink backpack 20 years ago. Now, I enjoy how the pastel rosiness surprises me as I look at it.

Sharpening includes the clothing.

I can be more than the black-wearing queer punk anarchist stereotype of my youth. First thing after arriving in Japan, I shopped for presentable summer clothes—another years-long area of growth Sensei has beckoned me into. No more black! More colour! I feel fresher, more cohesive. More confident, and a better support for her as we navigate Japanese society. Presentation matters. Form matters! A theme of our time, in a formful Kyoto.

At some point, I lean against a wall, and get black tar on my brand new white jeans…

We wind our way through the narrow streets, cicadas chirping, to the first Gion Festival float of the morning. I am focusing on keeping my radar on the Lama, like a field of awareness. Keeping in step with her field, looking over at her out the corner of my eye. Sensei walks confidently, often quietly and with a focused brow. Sometimes she turns to me and shares a history of this or that particular traditional storefront, or points out, Look: The beauty of a green lotus pad, sensitively present in a miniature pot pond, on the concrete pad at the foot of a concrete apartment building. We pause for a moment together in appreciation, exchange a chuckle at the contrast from Canada’s cowboy aesthetic.

We arrive upon a float, a ‘yamaboko,’ in action. Community members assemble it. Men of all ages, muscles bared, wind handmade ropes around solid wood beams, placed together like a jigsaw. They do it as it has been done by other men, for centuries. Every year.

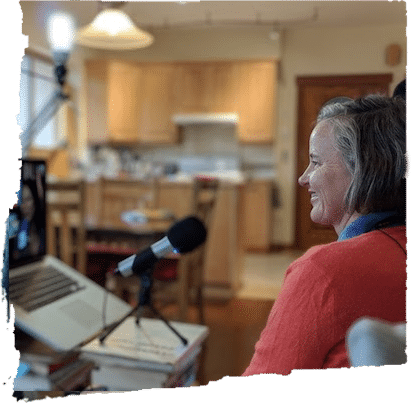

We stop twenty feet away from the towering structure and I set up the camera while Sensei takes in the surroundings. She says hello to some smiling old acquaintances, some who helped her with her research and book. She’s reintroducing the importance of the festival’s spiritual foundations, and the community of people who have kept it going for more than a millennia. I tuck the wireless mic into a fold in Sensei’s beautiful white linen kimono, the crisp weave and texture securing me to the material world. There are no lights, but camera and action happen next.

Sensei speaks, eyes smiling. “Hi, we are at Hōka Boko. Hōka means Buddhist itinerant monk; the type who would wander around the countryside giving spontaneous teachings. They were homeless, or at least we think they were. Sometimes they were very highly realised beings and sometimes they were sheisters who were trying to get people to think they were monks so they could collect money. So, it’s very interesting that this float neighborhood adopted these homeless monks as their theme.”

That’s a take! I am nervous, hoping the sound and camera angle will turn out. I don’t want Sensei to have to repeat herself.

What does it mean to be attendant to, in service of, your spiritual teacher? In reality, the teacher is always in service to you. Immensely, generously. It is a question of each moment. How is your concentration, diligence, awareness? How open is your heart? What needs to be done, next?

Next, Sensei points out some of the detail on the side of the float—in this case, a several hundred year old tapestry made by masterful artisans. A dragon emerges from handwoven silk threads, lines of silver, browns and blues. It peers through the clear plastic protecting it from forecasted rain with a wide open mouth, grinning.

All the floats display treasures that have been cared for over many centuries.

Often these treasures were acquired via the wealth and power of kimono merchants, whose prosperity during certain periods financed a great deal of the festival. Much changed in 19th and 20th century Japan, the Gion Matsuri evolving as it always has. Now, crowdfunding brings in needed finances, an example of a modern tool conserving tapestries and sculptures of antiquity.

I film some of the detail, trying to be as quick as Sensei’s feet—they begin to carry her on to the next float. My Lama field radar says: Time to move!

We continue to the next float and repeat this process, visiting as many as we can, a handful, until it is time for breakfast. There are 34 floats in the festival’s total procession. I hunker through, hungry and a little faint from the growing heat, trying to drop aversion and clinging. I wonder how Sensei is feeling. Do I ask?

We go to Sensei’s new favourite spot for breakfast: A delicious zero-waste buffet restaurant supplied by local organic farms. Fresh vegetables, miso soup, congee, and… espresso! All on offer for 550 yen—$5!

Eating with Sensei is meditation. I practise slowing my eating, watching habitual awkwardness and the impulse to fill the space with speech; I watch it arise, and pass away. I settle into the awareness of taste, texture, sensation and at the same time, the Teacher in front of me, who demonstrates graceful equanimity and enjoyment. Two people, their digestive systems doing their thing. Simple silence and sometimes words bubbling up from the source. We share about what we observed that morning, how we had felt, things we wondered. Sensei would check in on me, “How are you doing?”

On most days, good. Or great! On other days, nervous. Or emotional. Sometimes angry. Sometimes sad. Or scared. Old wounds, rubbing up against the rhythmic sandpaper of one’s Teacher’s penetrating mind.

In the path of this mind, our deepest fears, subtle and evaded in a myriad of ways. A dance, a fight, a non-negotiable negotiation on trust…

Some of my most painful moments in the Dharma have been with Sensei. I have felt she didn’t understand me, that she misunderstood me, behaved harshly with me. Much changed in the past couple of years, for the better; I had seen and admitted a lot of patterns I hadn’t clearly acknowledged before. Tried to apologise for my bullheadedness, aggression. We had some heart-to-hearts. But coming to Japan, it was a little rosy, a little too good to be true, a little too easy. Anything spiritually bypassed surely could not remain that way this trip.

Of all things that unearthed the old bones, it was a shopping expedition to the grocery store, a small communication lapse that triggered the storm of baggage clearing. Sensei wanted to meet a friend, so I said I’d go ahead, pick up some groceries, something for lunch. It had felt like a loose arrangement… I wandered around the grocery store awestruck by the smells, colours, tastes, picking out ingredients to cook for future dinners. I also picked up a box of sushi for our lunch. By the time I got back from the store, it had been an hour and a half since I’d left her.

Inside the entranceway of our machiya house, Sensei appeared in the clearing. “Did you get lost?” she asked. Something was in her eyes. I said… “No? Daimaru was just up the road.”

“You’ve been gone for hours.”

I tried to explain that I had been shopping with her in mind, to buy the best organic food, for her…

Yes, but you got so caught up in your need to make me the best organic dinner, you forgot to think that I might be hungry! You forgot to think about my well-being, here, today.

Inside, confusion, storm. It was true, my mind had wandered off, off from ‘sharp’ and attentive.

We moved further into the house. We got into older conversations that hadn’t gone anywhere in the past. She asked if I knew the impact I had on other people—did I know how my actions hurt others? I asked her if she’d felt hurt by me in the past. She said, what do you think? The answer was, yes. Numb, chest aching, I said, well, I have felt hurt by you, too. We sat in that silence. Tears like water slowly massaged out of a stone. The pain in the heart moved.

Not long after our intense conversation, something switched. I just stopped. Dropped the need to protect, of trying to coordinate myself around her as though always for an incoming attack. Or to appease, and garner, love. Exhausted by that swordplay, the mind shifted to: Okay. How can I help? What does she need? I careened like a spaceship travelling to new coordinates on the galactic starmap. Hyperspace.

And I saw that she is in one hell of a difficult position. What do I mean by that?

Imagine this. You are trying to help someone stuck in a maze, a castle of projection, a hall of mirrors. You have clarity, having already made the journey through it yourself. Yet, in the world of human form, physicality, conceptions, you are also all the time something of a mirage to this person. A mirage of their memories, hurts, previous perceptions. Why should I trust you? is the constant question on their mind, as you try to point out the stone wall they keep walking into, but can’t see.

This is a difficult position, particularly for women Teachers at this time in history. If I have learned anything from having a female Teacher and a diverse sangha, it is that my ping-pong ball reactions set off, bouncing in all directions with every contact made between us. Some ping-pong balls are more obvious and some are less conscious; some are painted bright yellow, and some are like ghosts.

So, when it comes to my interactions with women in leadership, a certain set of ping pong balls get set off. Do you know what I’m talking about? As spiritual practitioners, we can think we’re well beyond commonplace gender bias—of course I’m not a misogynist, I’m a holy, woke, feminist spiritual seeker! But, dear friends, after 18 years of yearly, long meditation retreats, and constant training in the Dharma with very awake Teachers, I am of the opinion that there are places in my consciousness that are thick like mud, and that the filters we wear run very deep, for decades!

Regardless of how ‘spiritual’ I think I am, I was brought up in a society and family with unexamined gender (and all sorts of other) biases. Were you born to a mother? One who both cared for and scolded you, a female figure, the authority, who moulded you from tantruming toddler into a functioning adult? If you did (or didn’t!)—you’ll have certain physiological responses to women. This is the case for me, and, no surprise, like clockwork these responses are mapped onto females of authority in my life; my first and oldest, deepest template for this being my mother.

One of the best ways to see this is in longer meditation retreats. For me, as the mind quiets, focuses, the body-mind becomes like an archeological dig—chunks of old metal imbedded in flesh, leakages from the heart, constrictions in the gut. Fear of annihilation, abandonment in my left shoulder blade; a numbness, a tightness, a stabbing pain… Memories of the young child in desperate and futile negotiation with mother. Four deep ego fears in action, and for me, often, fear of death.

My mother was a good person doing the best she could. But all our ‘mothers,’ as the one who birthed us, are also the universal source of life, of care, of nutriment. At depth we know, without her care there lies abandonment, annihilation, death. Sounds dramatic!

The question is, how do you write and live the screenplay of this potential disaster movie? What does your hero(ine) do to navigate life and death? How do you appease and differentiate from mother?

Another layer of this dynamic is how patriarchal history has appeared in Buddhism. About 20 years ago I started practising in sanghas accustomed to male leadership—Doug (Qapel) Duncan and Goenka Ji in my case. Think about the revered Buddhist ‘Gurus’ and prominent role models, modern and pre-modern—mostly men. Though great women peek through the Buddhist history books occasionally, think of the big spiritual names you know: The Dalai Lama, the 16th Karmapa, Namgyal Rinpoche, Sayadaw U Thila Wunta… Thich Naht Hanh, Suzuki Roshi, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, (Jesus Christ, Muhammad!)…the list goes on. The bias is immediate. It’s no one’s fault. As a young person I heard stories of Buddhist nuns in Asia praying to be born as men in the next lifetime, for greater spiritual attainment. All of this impacted me, and for a time on the path, I believed that to be a master meditator, you had to be a man. So if I felt I was not equal in potential to my male sangha brothers, how could I have the confidence in my female Teacher that I had for my male Teacher?

Through all of this, I see more clearly all the ways I have dismissed my female Teacher and the women in my life.

But we learn! (See also Women in Buddhism). The great boon of the seeking human consciousness. After the heart realises what it did not know and how it continued to act in ignorance, it can sing a mournful song as an offering, then turn it to a joyful one; the eyes look up, brighter. There is power in awareness, acceptance, letting go. Knowing what is, what has been, the ways we suffer, cannot be dismissed – as it is all making up the walls of the castle on which we are (a)mazing our way through – from which we stand upon to obtain a mightier view.

Sensei is Sensei. Just her. Who she is. A wise being, cloaked in a caucasian mid-Western American woman’s body, and all the projections we apply to it, trying to help. And I am who I am. With my set of lenses, biases, hurts, looking at her as clearly as I can. Yes, she is direct, intense, concentrated, and highly principled. Demanding of her students. Also caring, thoughtful, methodical, and inquisitive. And in me, some traits trigger physiological fears, while others open my mind to new ways of looking. There will always be projection with Teachers, because humans are projection machines. So the best I hope to do as a student of consciousness is to love and appreciate my Teacher for her service, her wisdom, her talents, the spiritual work she has done. And, to have compassion for all involved in the messy game of waking up. As Qapel and Sensei said about Vajrayana teaching in a recent meditation retreat on the 12 Manjushris: Not everything works out perfectly. Teachers make mistakes, too. But if you have faith that you’ll unfold no matter what happens, you will. If you think you’re going to get hurt, you will. As the Zen saying goes: six times fall down, seven times stand up.

Back to the room—sitting on the tatami, on the floor. The storm passed. We moved on.

One day, after our morning filming, Sensei looks up from her natto and congee breakfast and says, “I’m going to take you somewhere special.” We catch the subway, then a taxi, and soon we are at Daitokuji, Kyoto’s historical Rinzai Zen monastery. The hairs on my body stand up, in salute! Over the past three years, I had earnestly attended Qapel and Sensei’s Zen and Chan courses and retreats. Some of the illustrious and eccentric figures they had spoken of— such as Ikkyū—had walked, practised, and recorded their famous koans in this very place!

Walking through the cedar entrance gates, I follow Sensei again, my meditation beacon, tuned in with her body, her posture, her pace, her gait. Silencing my mind when necessary, responding to her inquiries, asking questions of her as they arise. She leads us through the broad, pebble sculpted walkways to Zuihoin, a sub-temple built in 1535. We have an appointment with her friend, the abbott there. The attendant, an earnest faced young Japanese-American whose mother, a tea ceremony teacher, has sent him there to learn, shows us to the tea room to wait.

I am tight with self-inflicted pressure. Sensei mentions we are actually at the historical birthplace of the tea ceremony tradition. No big deal! My body remembers the exacting postures of the formal tea ceremony I’d once attended in Tokyo. What will this master abbot be like? I wonder. Will I stumble on the formalities of the ritual? Will I forget to turn my tea bowl in the right direction? How to not make a fool of myself, not embarrass Sensei?

Well, I needn’t have worried, because in comes the abbott, looking like a good friend you might visit the beach with. He is glad to see Sensei. They have known each other a long time. He starts to prepare our matcha green tea by heating a kettle of water over hot coals. His father, the former abbott, comes by at one point. Also Sensei’s old friend, head shaved with a broad chested energy and shining cheeks, he gives a hearty greeting, “Konnichiwa!” though Sensei shares that as he has grown older, he doesn’t remember her as clearly. His son speaks to Sensei about how that transition has been for them all. My ears and brain perch attentively trying to follow the conversation with my very limited high school Japanese.

The younger abbott serves us tea. It is informal! I don’t have to sit on my feet until they go numb! He encourages us to get comfortable. I look over at Sensei, trying to follow her lead. I nod and smile, repeatedly, as I can’t find many words in Japanese. For today, “Thank you, hello, I work as an acupuncturist,” and “She’s my meditation teacher,” will have to suffice.

We enjoy two cups of matcha, each served in a one of a kind bowl. I soon learn that these we are using today are Shigaraki ceramics, renowned as one of Japan’s six ancient kilns. With a rough-hewn texture, they feel like I’m drinking out of the earth itself. Alongside the tea, we taste the intense flavours of sweet, then salty, first with a delicate sweet bean dessert, a sailboat on a summer lake, and then some temple-made fermented black soybeans, sharp like an axe slicing winter kindling. When our gentle time together in this tatami room comes to a close, the abbott farewells us and we move on to visit the Zuihoin zen garden.

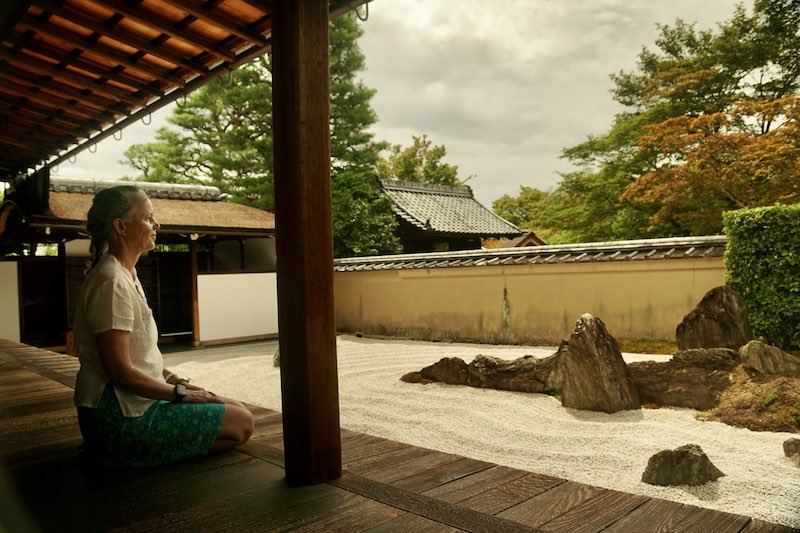

I follow Sensei around the building, the skin of our bare feet kissing the dark wood floors, smooth from centuries of foot service. As we turn the corner, a Zen rock garden comes into view. There is no one there but us, and we find a seat under the roof’s wooden eaves.

Looking out over the grey pebbles that curve, precisely raked into an ocean, lapping up against the landmass of moss covered rocks, I feel swept away. Swept into the ocean.

It moves, pulsates. I can hear the sea, the shore. I can hear life, alive! I have seen plenty of rock gardens prior to this… but never really saw, never really heard, felt. Form. It is alive!

I weep, part of the ocean. Alive. The joy.

Sensei stands slowly. I follow her into the meditation hall next to the zen garden. She shows me the ancient paintings, black ink on the washi paper walls, some faded, some slightly torn. Tears come, the waters moved. I cry and cry from the feeling of the room. All the people who meditated here, who cared for it, painted it, practised, prayed, grappled with koans, dedicated themselves to awakening… I feel them in the air, in the walls. My heart drops, sinks into the past, swims with the Dharma ancestors, appreciates, feels thankful for. What we put our energy and care into can carry through the ages.

Sensei and I meditate here a while. Silence, stillness. Form, emptiness. History. Compassion.

With gratitude to Sensei, Qapel, Namgyal Rinpoche, lineage, to transmission, to the power of sangha, the teachings of awakening, and the awakening that dwells in all beings.

At some point, the Teacher’s presence and steadfastness allows the student’s guarded heart to have the confidence to surrender. At that time, you are flooded, overflowing. With what? With life? That is transmission. It is a transmission of the oceanic heart. That is the beauty of Guru Yoga.

And a precious thing.

Want this year to be an awakening one?

Sign up for our 52 reflections, bite-sized weekly wisdom.